Empty snack tins. They once held popcorn or Holiday cookies.

Now, they’re gathering dust in our garages and attics. Most people throw them

away, but not us. We will repurpose

them. At least, that’s what we tell ourselves year after year as a few become too

many.

At some point, we admit defeat and realize the tins are

transforming into nothing but clutter. Still, they are too nice to discard. Someone

else might want them, we tell ourselves. We slap masking tape price tags on entire

boxes of them, set them out at our garage sales, and pray for a Pinterest

princess to descend from the heavens. She will wave her magic wand and turn

them into planters, candles, organizers, and sewing kits.

We sit in the bleaching sun all day, selling shirts for a

dime and empty frames at two for a buck. The sun finally sets . . . and we face

the inescapable truth: nobody wants our tins. This surprises us, and we begin

to wonder (again) how we became such a throwaway society.

It wasn’t always like this, as I learned while researching

my latest novel, SCATTERED SEEDS. Colonials wasted nothing, thanks to poverty

and the scarcity of basic necessities. I found many instances of want

documented in colonial records. I included one of the most striking examples in

this scene:

“Who are you?” A girl aimed a gun twice as long as she was

tall. She was naked except for a short buckskin skirt with a crooked hem and

the threadbare collar from a man’s shirt.

Edward looked away from her bare breasts, shock stealing his

words. She was fully developed, probably five-and-ten years old.

“I’m gonna ask you one last time. Who are you?”

Edward could not meet her eyes. He stared at her bare feet.

They were filthy and calloused. “My name is . . . Lassie, I have a blanket. Let

me go back to my packs and—”

She pulled the hammer to full cock.

“I didn’t ask you for no blanket. I asked you for your

name.”

The idea of

finding Clara Tanner half-naked in the wilderness came to me as I read an 18th

century clergyman’s journal detailing his travels through what was then the

frontier of Pennsylvania. The reverend found indescribable poverty among the

settlers eking out an existence in the vast forest. He reported entire families

clothed in nothing but the remnants

of garments, as if wearing threadbare collars alone somehow preserved dignity

and set them apart from the native inhabitants they deemed savage.

Another

colonial traveler witnessed a man carefully saving the threads from a ruined

shirt. That made it into the novel, too.

Henry stripped off his shirt and tossed it in a bloody heap

next to the hearth. The garment was good for nothing now but char cloth and

spare threads, same as his old neckerchief.

I disliked waste before I researched this novel. I hate it

now. I find it difficult these days to throw away anything. Today, I made a

salad, and I couldn’t bring myself to toss away the lettuce stump without at

least trying to grow another head from it. I asked myself, “What would my

characters do?” Of course, they would opt to plant it.

I will never save the earth by planting a lettuce butt. In

fact, my feeble efforts to decrease the size of my footprint will certainly go

unnoticed. But I strongly feel my attempt to minimize my impact on the world

isn’t just the right thing to do—it honors those who came before me, those who

would have given anything for a taste of fresh lettuce.

Here’s a picture of my planting, my first attempt at

re-growing lettuce from a stump. I would love to know if any of you had success

with this. I hear you can do it with celery, too. Ideas? Let’s have ’em!

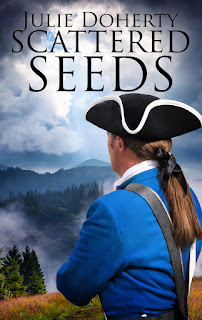

Scattered Seeds

Julie Doherty

Genre: Historical fiction, elements of romance

Publisher: Soul Mate Publishing

Date of Publication: April 27, 2016

ISBN: 1-68291-050-4

ASIN: B01E056H1Q

Number of pages: 339

Word Count: 100,000

Cover Artist: Fiona Jayde

Book Description:

In 18th century Ireland, drought forces Edward and Henry McConnell to assume false names and escape to America with the one valuable thing they still own–their ancestor’s gold torc.

Edward must leave love behind. Henry finds it in the foul belly of The Charming Hannah, only to lose it when an elusive trader purchases his sweetheart’s indenture.

With nothing but their broken hearts, a lame ox, and a torc they cannot sell without invoking a centuries-old curse, they head for the backcountry, where all hope rests upon getting their seed in the ground. Under constant threat of Indian attack, they endure crushing toil and hardship. By summer, they have wheat for their reward, and unexpected news of Henry’s lost love. They emerge from the wilderness and follow her trail to Philadelphia, unaware her cruel new master awaits them there, his heart set on obtaining the priceless torc they protect.

Book Trailer: https://youtu.be/bNzrVFnl9Ts

CHAPTER

1

County Donegal, Ireland

1755

Henry stood next to his father

surveying their largest field. He longed to say that the seeds might yet

sprout, that there was still time to yield a return, but the undeniable truth

lay right before them: drought had come to Ireland. Their investment in imported

flaxseed was lost.

“A hundred days, Henry.” Father’s

face bore the pained expression of a man whose hope was as withered as his

crops. “A hundred days was all we needed, all that stood between us and prosperity.”

He kicked a clod of dirt, and it turned to dust. “It’s all gone, gone along wi’

the horse that harrowed the ground.”

A lump rose in Henry’s throat. He

ached for his father, and he missed their horse. Paddy was a fine animal

purchased ten years ago after a bumper crop of rye, when Edward McConnell’s

luck was good and Henry’s only chore was to stay out of his mother’s hair.

Elizabeth McConnell moldered in the ground now, and Paddy plowed another man’s

fields.

“We will pray, Father. God will

help us.”

“God?” Father kneaded his

forehead with calloused fingers. “God’s groping in our pockets right along wi’

your Uncle Sorley. Praying did nae pay our tithes or the hearth tax, did it?”

Surely he didn’t mean that.

Everyone knew Edward McConnell to be a godly man.

“We’ll get more seed, Father.

It’ll grow next year.” He squared his shoulders and tried to look confident.

“Will nae do us any good. Your

Uncle Sorley plans to decrease our tillage in favor of pasture.”

“Wi’ no cut in rent, I’ll wager,

and early payment again this year.”

Father spat on the parched

ground. “He stopped by yesterday looking for it. Said he’ll call in after

services on the Sabbath.” He ground his teeth together. “I’d gi’ anything to

see the look on his face when he finds our empty hoose.”

Henry’s chest tightened. Were they moving again? He rubbed the

back of his neck and looked across the rolling patchwork of fields to the

northeast, where their last home rose above a copse of ash, and where his

mother’s daffodils still swayed in the Ulster wind. Four years ago, the cattle

plague put them out of that house and into the windowless shack they now shared

with Phoebe, their only remaining sow. The hut contained a hearth, a curse

necessitating the payment of tax despite the fact that it never contained a

fire.

With no peat left and no horse to

haul more from the bog, the McConnells relied on a moth-eaten blanket and

Phoebe’s body heat for warmth.

They had room to fall; many

Catholics lived in the open, bleeding cattle and boiling the gore with sorrel

for sustenance. Perhaps his father intended to join them.

“Are we moving again?” he asked.

Father slipped two fingers under

his brown tie wig and rubbed his temple, something he often did when puzzled.

Henry followed his gaze to the

ruins of Burt Castle, which sat atop a knoll, just above Uncle Sorley’s grand

plantation house.

“Nine years we’ve suffered bad

luck, Henry. E’er since I buried . . .”

Buried

what? Maw? She died five years ago, not nine.

Father sunk his head into his

hands, muffling his speech. “I . . . I guess it’s time to . . .”

Henry stepped into the hard, hot field,

directly in front of his father. “Father, what in the name of heaven is it?”

Father tilted back his head and

whispered to the sky, “Forgive me, Elizabeth.” He looked at Henry. “I buried

something. Your maw insisted on it, said it was pagan and she did nae want it

in her hoose. I did as she asked. A woman can talk ye into cutting off your own

hand, Henry, remember that if ye can.”

Henry nodded, not comprehending,

wondering what pagan thing lay buried. He’d never heard it mentioned before,

and he was a skilled eavesdropper. “What was it? What did ye bury?”

Father inhaled deeply, removed

the worn tricorn from his head, and tucked it under his arm. “I’ll tell ye the

whole tale, but first, we have to dig it up. We canny do that until after

dark.” He turned without warning and headed for home.

Henry followed him, volleying

questions against his back.

Father said nothing until they

reached their hut. There, he stormed past Phoebe, flung open the door, and

nodded toward a worm-ravaged chest sitting next to a heap of rushes that served

as their bed.

“Gather up our claithes and

shoes. Use my good cloak for a sack. Bring the dried nettles.” He grabbed the

peat spade, the only tool left from his once abundant array of implements, and

used it to prop open the door.

“Why bring the nettles?” Henry

hated the bitter leaves. “There are more nettles than rocks in Ulster.”

When his father offered no reply,

he lobbed another question, desperate for clues as to their destination. “Will

ye not wear your good cloak, if we are traveling far?”

“My auld cloak will draw less

attention.”

So, they were going to some

populous place where good cloaks were bad.

Henry spread the cloak across the

dirt floor, careful to avoid Phoebe’s manure. The cloak was long out of

fashion, but still a quality garment that Edward McConnell could not afford to

replace. He threw their scant belongings into the middle of it, brought the

cloak’s corners together, then tied them together to form a sack. Excepting

Phoebe and the clothes they wore, the sack contained everything worth saving.

He sat on the rickety chest to

watch his father pace.

When Burt Castle became a

silhouette against an amber horizon, Father donned his hat and cloak and ducked

outside.

Henry followed him to the stone

wall separating their field from Uncle Archibald’s.

Father began to tumble a section

of wall.

With his perplexity and fear

mounting, Henry assisted until there was enough of a breach to push Phoebe

through the wall.

She trotted away, grunting and

wagging her curly tail, while he helped restack the stones to prevent her from

returning.

He could no longer hold his

tongue.

“What are we doing? Why are we

putting Phoebe in Uncle Archibald and Aunt Martha’s field? Are we going

somewhere? Where are we going? Why are we taking nettles?”

In his frustration, he grabbed

his father’s arm.

Father whirled around and gave

Henry’s shoulders a fierce shake. “Get hold of yoursel’, lad, or I’ll cloot ye

upside the noggin. No more questions. Just do as ye’re told.”

Henry stared at his father, who

had never once laid a hand on him, nor threatened to.

“I’m sorry, lad. Go on in the

hoose and get the bundle.”

When Henry returned with their

belongings, his father was holding the peat spade.

“Get a good look around ye, son. It’s

the last time ye’ll clap eyes on your hame.”

About the Author:

Julie Doherty expected to follow in her artist-father’s footsteps, but words, not oils, became her medium. Her novels have been called “romance with teeth” and “a sublime mix of history and suspense.”

Her marriage to a Glasgow-born Irishman means frequent visits to the Celtic countries, where she studies the culture that liberally flavors her stories. When not writing, she enjoys cooking over an open fire at her cabin, gardening, and hiking the ridges and valleys of rural Pennsylvania, where she lives just a short distance from the farm carved out of the wilderness by her 18th century “Scotch-Irish” ancestors.

She is a member of Romance Writers of America, Central Pennsylvania Romance Writers, Perry County Council of the Arts, and Clan Donald USA.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SquareSails

1 comment:

Thanks for allowing me some space on your wonderful blog. My little lettuce is up about 5" already!

Post a Comment